Written by our student writer, Raghad.

Everyone forgets things from time to time, whether it’s why you walked into a room or a name you’ve known for years. The question is: when are these moments part of normal aging, and when do they signal something more?

As the world’s population is growing older, it is imperative that clinicians, researchers, and patients understand how to differentiate normal cognitive aging from pathological cognitive aging. This differentiation is crucial, as distinguishing normal cognitive aging from pathological aging is particularly difficult in older adults with cognitive decline. Many of the signs and symptoms of neurodegenerative diseases are similar to those experienced during the normal aging process, and this distinction is increasingly important as global life expectancy rises and the prevalence of age-associated disorders, particularly dementia, continues to grow (Murray et al., 2013). Understanding the differences between normal aging and pathological aging will help to ensure that older adults receive accurate diagnoses, proper treatment, and the support they need to continue to live independently.

Normal Aging

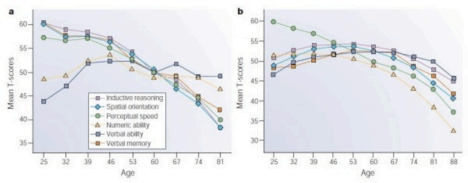

Normal cognitive aging is characterized by minimal and gradual declines in cognitive functions that do not significantly interfere with an individual’s ability to perform their daily routines or maintain their independence. Common areas that show the effects of normal cognitive aging include: processing speed, working memory, and some aspects of executive function (Hedden & Gabrieli, 2004). In contrast, there are some areas of cognition that show little to no decline due to normal aging, including vocabulary, semantic knowledge, emotional regulation, and autobiographical memory (Folstein & Folstein, 2010).

In terms of neurobiology, normal aging results in minor synaptic changes, mild neuroinflammation, and changes in neurotransmitter systems. The changes associated with normal aging occur without extensive neuronal death and are usually followed by compensatory mechanisms, including the use of alternative neural pathways (Hedden & Gabrieli, 2004). Consequently, the cognitive decline associated with normal aging is generally slow and non-progressive.

Pathological Aging

Pathological cognitive aging is the term used to describe age-related cognitive and functional changes that occur as a result of disease. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of pathological cognitive aging. It is a neurodegenerative disease that is characterized by increased memory loss, declining executive function, and dependence on others for the completion of daily routines (McKhann et al., 2011). In contrast to normal aging, pathological aging is characterized by rapid declines in cognitive function, domain-specific impairment, and interference with an individual’s ability to complete their daily routines

There are four main neuropathological features that have been traditionally associated with AD: amyloid-β plaques, tau tangles, synaptic dysfunction and chronic neuroinflammation (Denver & McClean, 2018). These features are often associated with impaired learning, decreased cognitive

flexibility, and decreased spatial navigation, which are greater than the typical declines that are observed in older adults with normal cognitive aging

Figure 1: Cross-sectional and longitudinal estimates of age-related change in cognition. Hedden, T., Gabrieli, J. Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 5, 87–96 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1323

Continuum Between Aging and Disease

It has become increasingly recognized that there is a continuum of cognitive aging, as opposed to two distinct categories of normal and pathological aging. This is due to the fact that many of the neuropathological features of AD can be found in older adults who are cognitively intact. The presence of amyloid plaques and tau tangles does not always correlate with the degree of cognitive decline (Price & Morris, 1999; Savva et al., 2009). Because of this, there is a growing consensus to view the relationship between normal cognitive aging and pathological cognitive aging as a continuum rather than a binary classification system. This continuum includes normal cognitive aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and pathological cognitive aging.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

MCI is an intermediate point on the continuum of cognitive aging, characterized by noticeable declines in cognitive function that are greater than expected based upon an individual’s chronological age, but less severe than those required to meet the criteria for AD. Individuals with MCI have a higher likelihood of developing AD compared to individuals without MCI, but this is not inevitable (Petersen et al., 1999).

Recent Research Trends and Advances in Understanding

In recent years, research has begun to shift focus away from using traditional pathological markers to diagnose neurological disorders to understanding mechanisms of cognitive decline. Some of the mechanisms that have been shown to be correlated with cognitive decline include: synaptic loss, soluble amyloid and tau oligomers, impaired insulin signaling and neuroinflammation. These mechanisms appear to be more directly related to cognitive decline

than the amount of amyloid plaque or tau tangle burden alone (Denver & McClean, 2018). Some cognitive domains have been proposed to be more sensitive to pathological aging than to normal aging. Spatial learning and navigation have been proposed to be early indicators that distinguish

AD and MCI from normal aging (Coughlan et al., 2018). These findings have significant implications for early detection and assessment strategies.

Limitations and Ongoing Challenges

While significant advances have been made in our understanding of cognitive aging and its relationship to pathological aging, there are still several major limitations to our current understanding. There is currently no single biomarker that can reliably distinguish normal cognitive aging from early-stage neurodegenerative disease. There is considerable inter-individual variability in both cognitive aging trajectories and neuropathological burden (Denver & McClean, 2018). Many of the current diagnostic tools lack sufficient sensitivity to detect cognitive decline in the preclinical stages of disease, when intervention may be most effective. The over-reliance on pathological markers that poorly correlate with clinical symptoms has also contributed to inconsistent findings and the failure of therapeutic trials aimed at reducing amyloid pathology burden.

Why This Matters to Patients

For patients and their families, differentiating between a normal age-related cognitive change and a pathological cognitive change is important because of the potential significant psychological and practical implications. While most of the normal age-related cognitive changes are non-threatening and easily managed, pathological cognitive changes require medical treatment, planning, and ongoing support. Misdiagnosing normal age-related cognitive changes as a disease may result in increased emotional distress and stigmatization for patients and their family members, and failure to recognize pathology may delay both a proper diagnosis and needed medical treatment. A clear distinction will allow for more realistic patient education, better monitoring, and better informed decision-making by patients and their healthcare providers. Additionally, it will help society have a more balanced view of aging, which views cognitive changes as a natural aspect of life rather than equates aging with inevitable cognitive decline and/or disease.

References

Coughlan, G., et al. (2018). Spatial navigation deficits—overlooked cognitive marker for preclinical Alzheimer disease? Nature Reviews Neurology, 14(8), 496–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0031-x

Denver, P., & McClean, P. L. (2018). Distinguishing normal brain aging from the development of Alzheimer’s disease: Inflammation, insulin signaling and cognition. Neural Regeneration Research, 13(10), 1719–1730. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.238608

Folstein, M. F., & Folstein, S. E. (2010). Mini-mental state examination. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(3), 203–205.

Hedden, T., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2004). Insights into the ageing mind: A view from cognitive neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1323

McKhann, G. M., et al. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 7(3), 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005

Petersen, R. C., et al. (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Archives of Neurology, 56(3), 303–308. Savva, G. M., et al. (2009). Age, neuropathology, and dementia. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(22), 2302–2309.

Leave a comment